When I think about movement, I often think about Pekiti Tirsia Kali--the lines, the angles, the timing. But long before I ever picked up a baston, my first lessons in footwork were already written into my family's history, passed down quietly through the stories my grandma shared about her life during World War II.

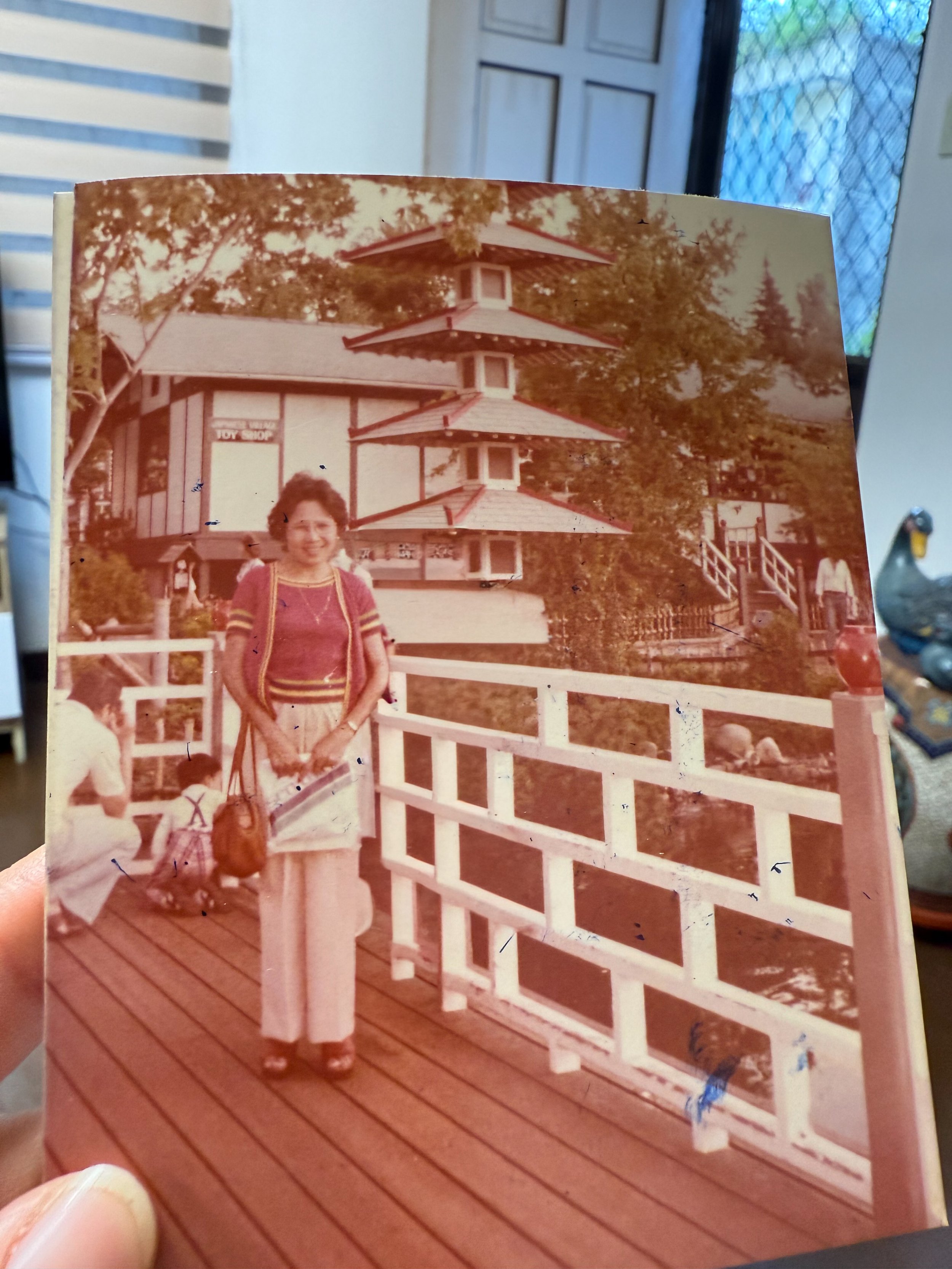

Grandma before the accident. This was in 1982.

Growing up, she used to tell me how she rubbed soot on her skin to make herself unappealing to the Japanese soldiers. I must have been around ten years old. At that age, the meaning didn't land. I couldn't grasp why anyone would need to hide their beauty just to survive, or how war twists ordinary life into something unrecognizable.

All I knew back then was that my grandma leaned on a cane, and for as long as I could remember, that cane was part of her silhouette. After her car accident in 1988, she was left with a disability that never fully healed. I used to wonder why the doctors didn't "fix it." I didn't know what it meant to live with an injury that would follow you for the rest of your life.

Yet somehow--this woman who seemed slow around the house--could take off with surprising speed when I threw away her cigarettes. She chased me through the living room, around furniture, and nearly onto the street, cane swinging in rhythm. Even with a bad leg, her footwork had purpose. Even then, her body remembered things I didn't yet understand.

It wasn't until I went through ACL surgery that I finally understood the gravity of her strength. The discipline. The endurance. The quiet willpower it takes to walk--let alone run--on a leg that fights you every step. And that insight came with the privilege of modern medicine, guided physical therapy, and resources she never had.

My grandma healed through necessity and survival. And survival creates its own kind of footwork.

When I began training in PTK, something shifted. The art gave me permission to look backward, to ask my parents about stories that lived in our family but were never written down. That's when I asked about the wartime memories my grandma would mention in fragments, like pieces of a larger picture she wasn't ready to describe.

My mom filled in the rest.

When Japanese soldiers began invading the provinces, my grandma's family heard gunshots and explosions in the night. There was no plan--only instinct. They grabbed what they could carry, balanced what they could on their heads, and fled into the mountains under complete darkness.

Top row (Left to Right): Uncle Pancho, Uncle Oscar, Uncle Jr, Uncle Freddie

Second row (Left to Right): Grandma Teresa, Auntie Sabing, Grandpa Teopisto, Great Grandpa, Mommy, Uncle Toto

Bottom Row: Uncle NickNick

My grandma?

She ran with a hot pot of rice balanced on her head--because they didn't know when they would be able to eat again.

Imagine that.

The weight.

The heat.

The urgency.

Running barefoot, in the dark, up uneven terrain with gunfire behind you--all while trying not to spill the only food your family has left. That's not footwork taught in a training hall. That's footwork forged from fear, courage, instinct, and the will to keep your family alive.

PTK teaches us the W-step, M-step, the hourglass, the cross-step--but these movements existed long before they were named. They were embedded in how Filipinos moved through forests, fields, and mountains. My grandma's steps through the darkness were the same principles we train today: balance, timing, awareness of terrain, controlled urgency.

Her footwork was the original survival pattern. Mine is the echo.

Now, when I train, I think about her. I think about the soot, the cane, the accident, and the sprint after my ten-year-old self. I think about the hot pot of rice, the darkness, the mountains, and the gunshots she outran. I think about how her body held stories her voice wasn't always ready to share.

And I realize:

The footwork I practice today mirrors the footwork she lived.

Her steps carved a path so that mine could exist.

Through PTK, I'm not just learning how to move--I'm learning how to remember.

Every time I step, pivot, shift, or slide, I honor the women who moved in the night so our family could see the morning.