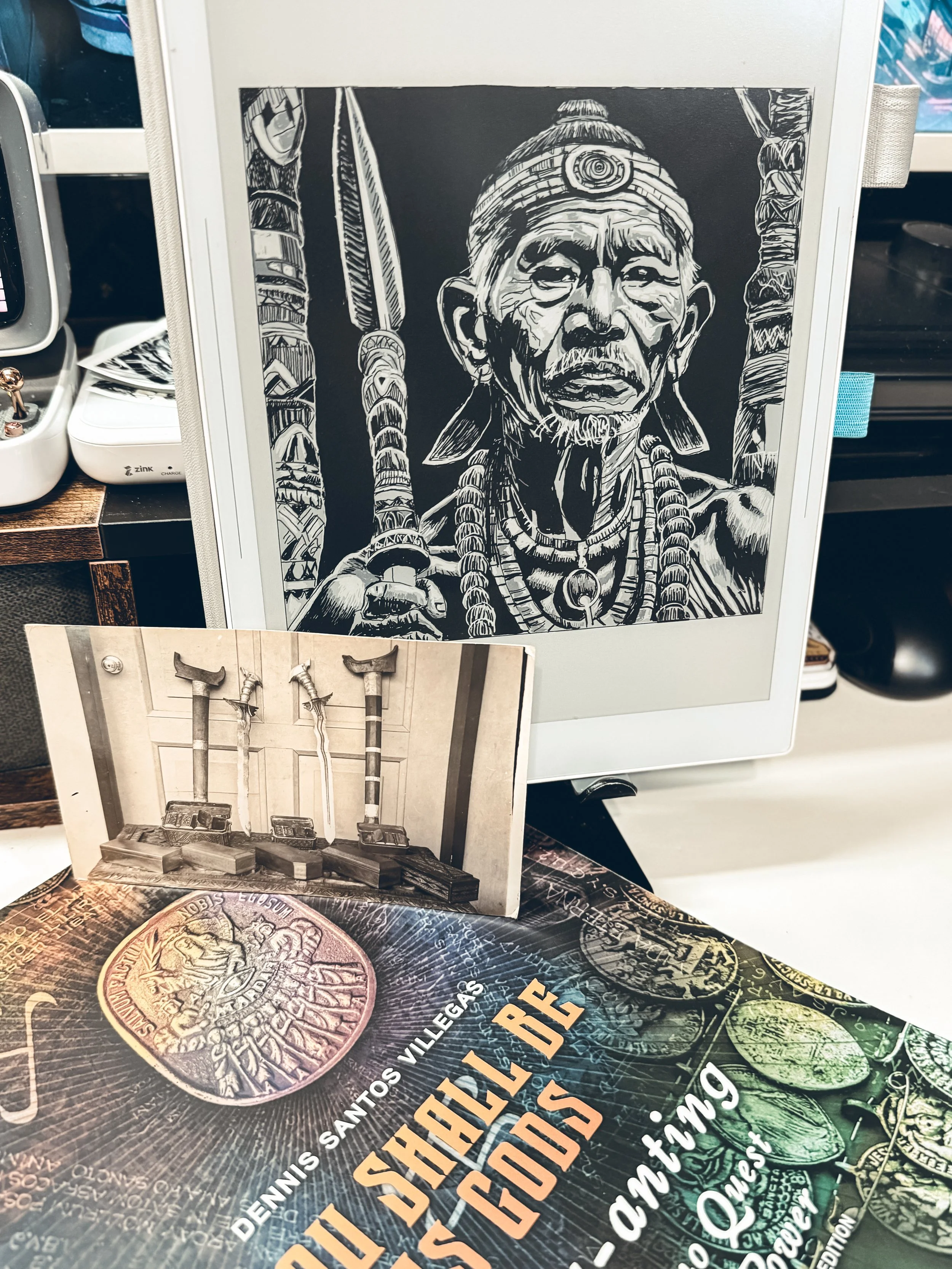

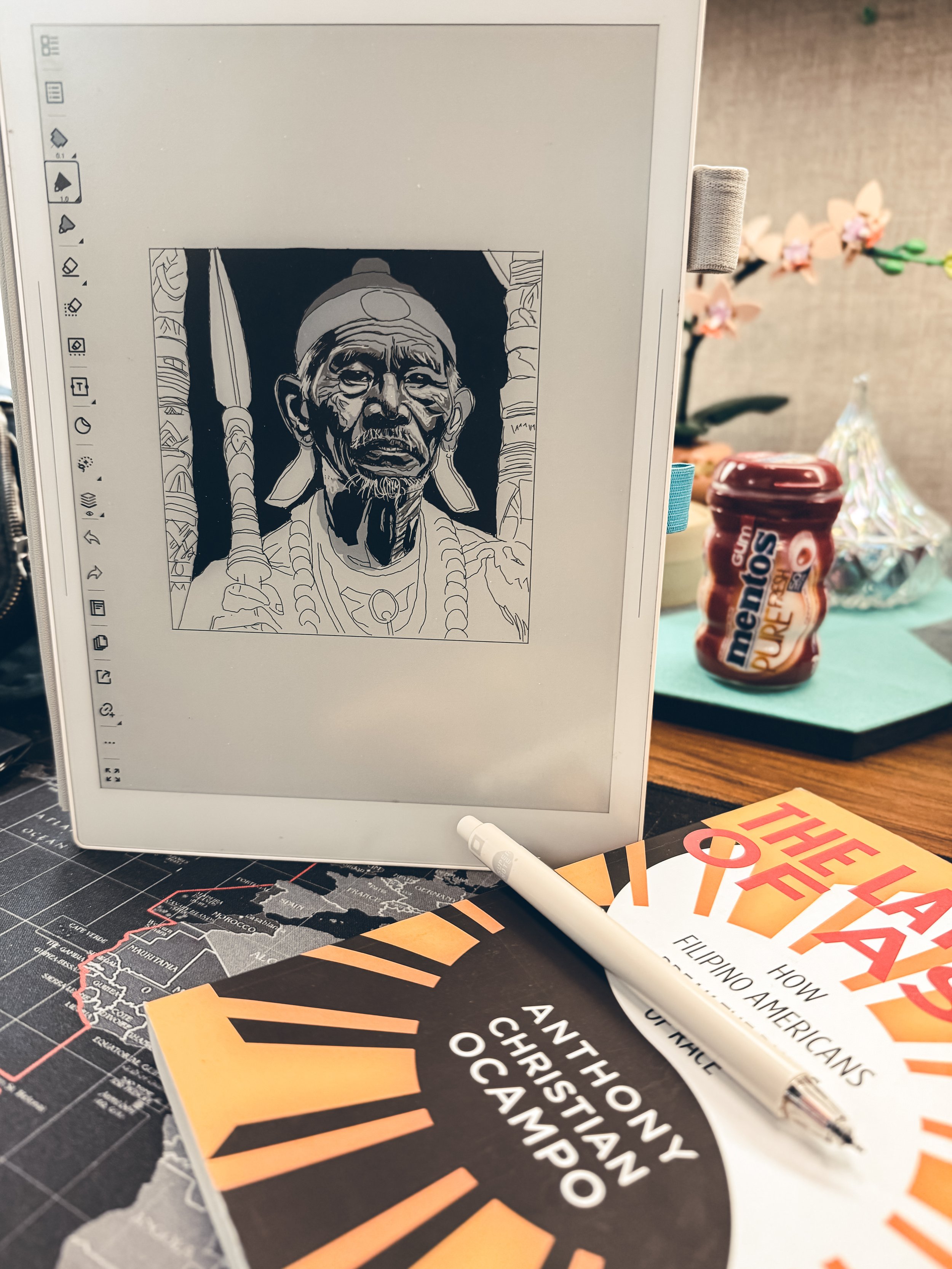

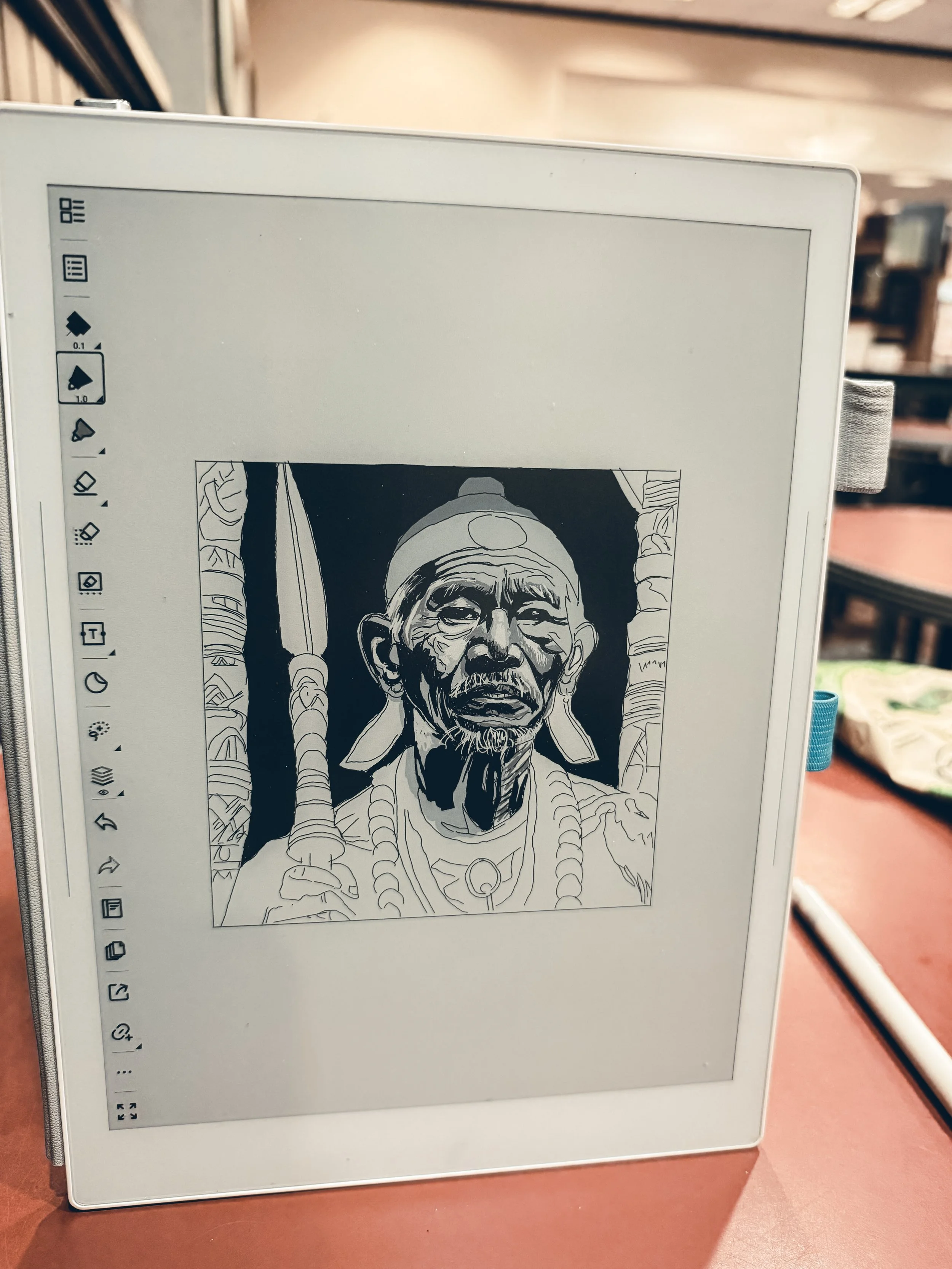

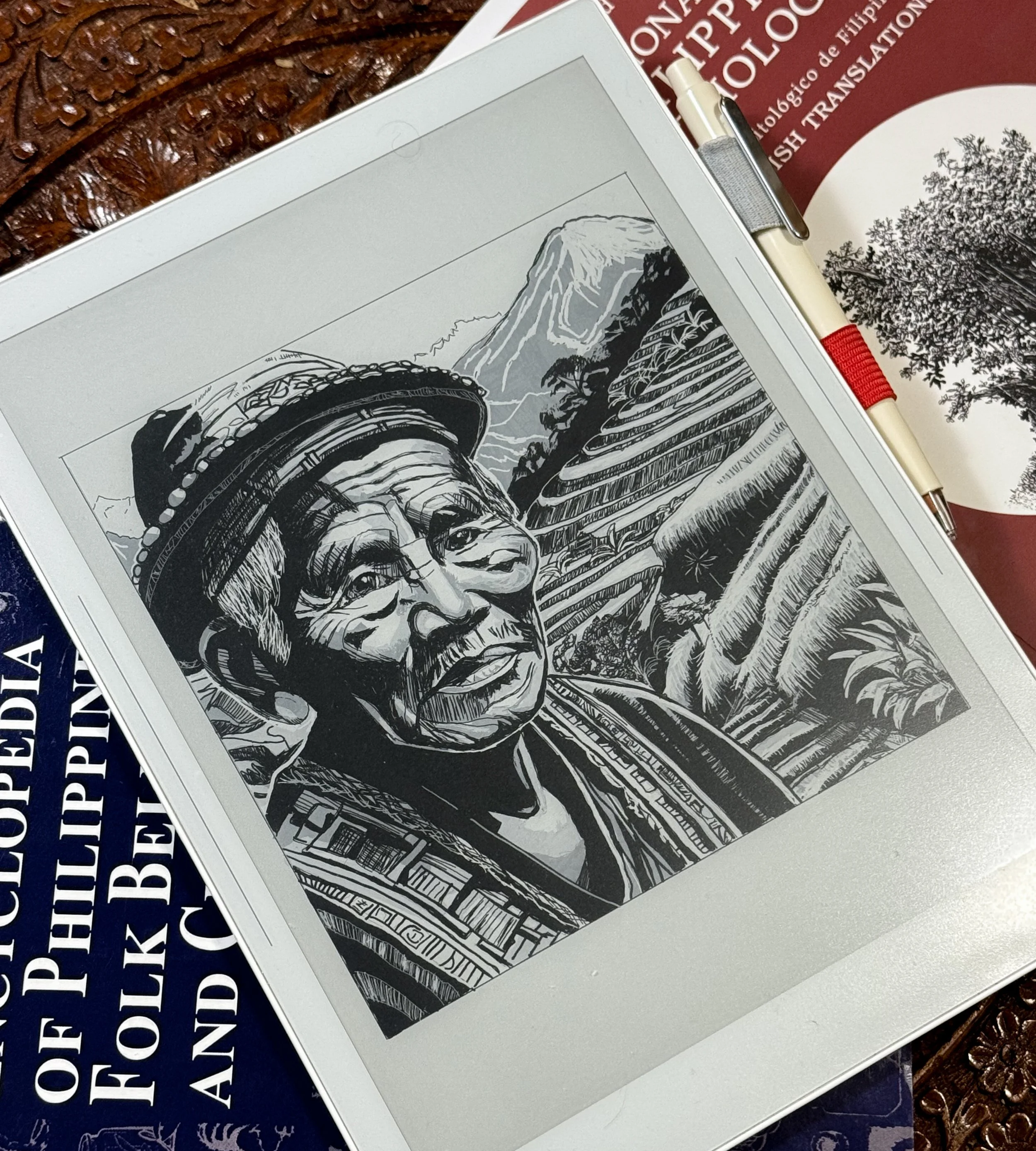

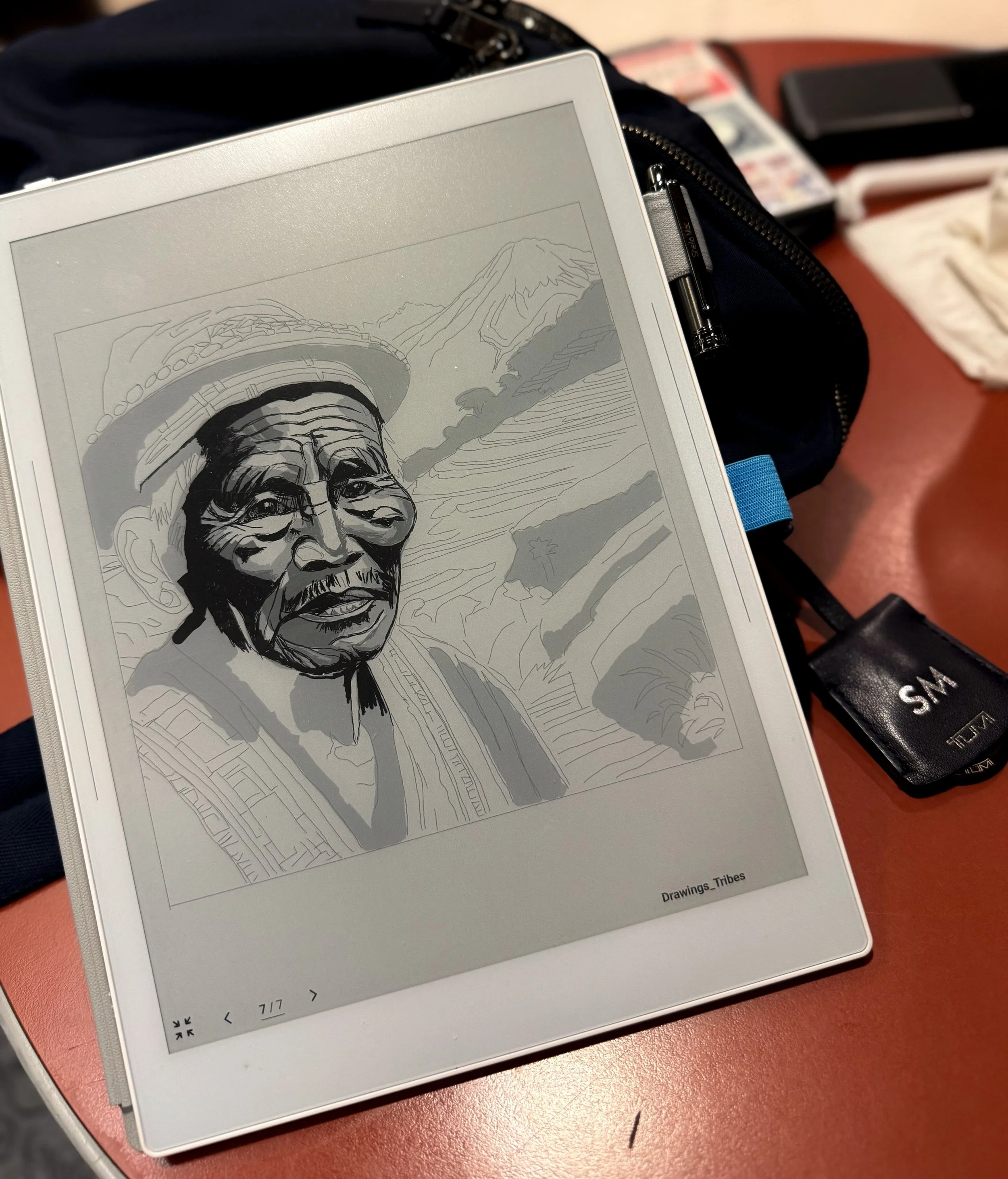

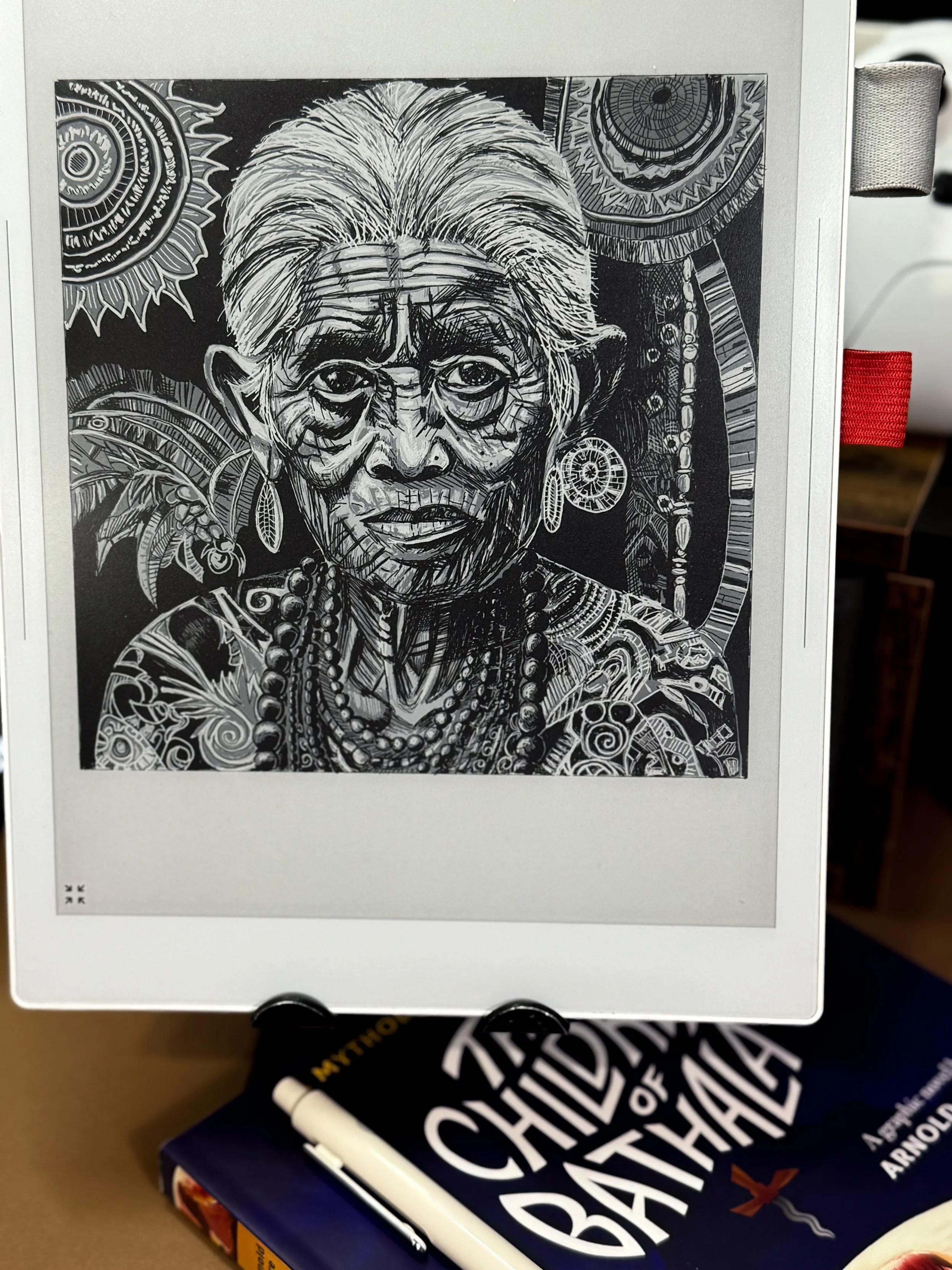

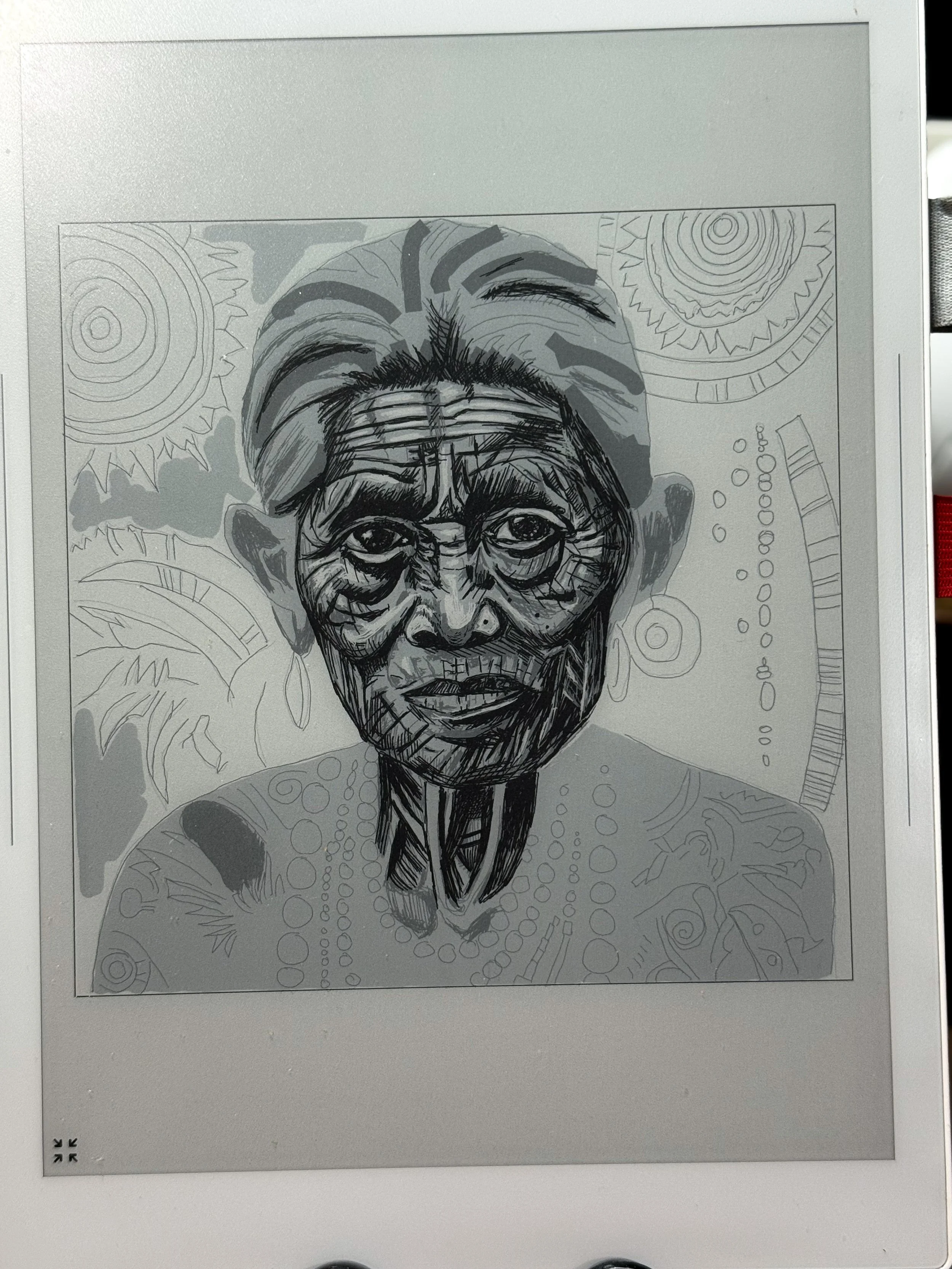

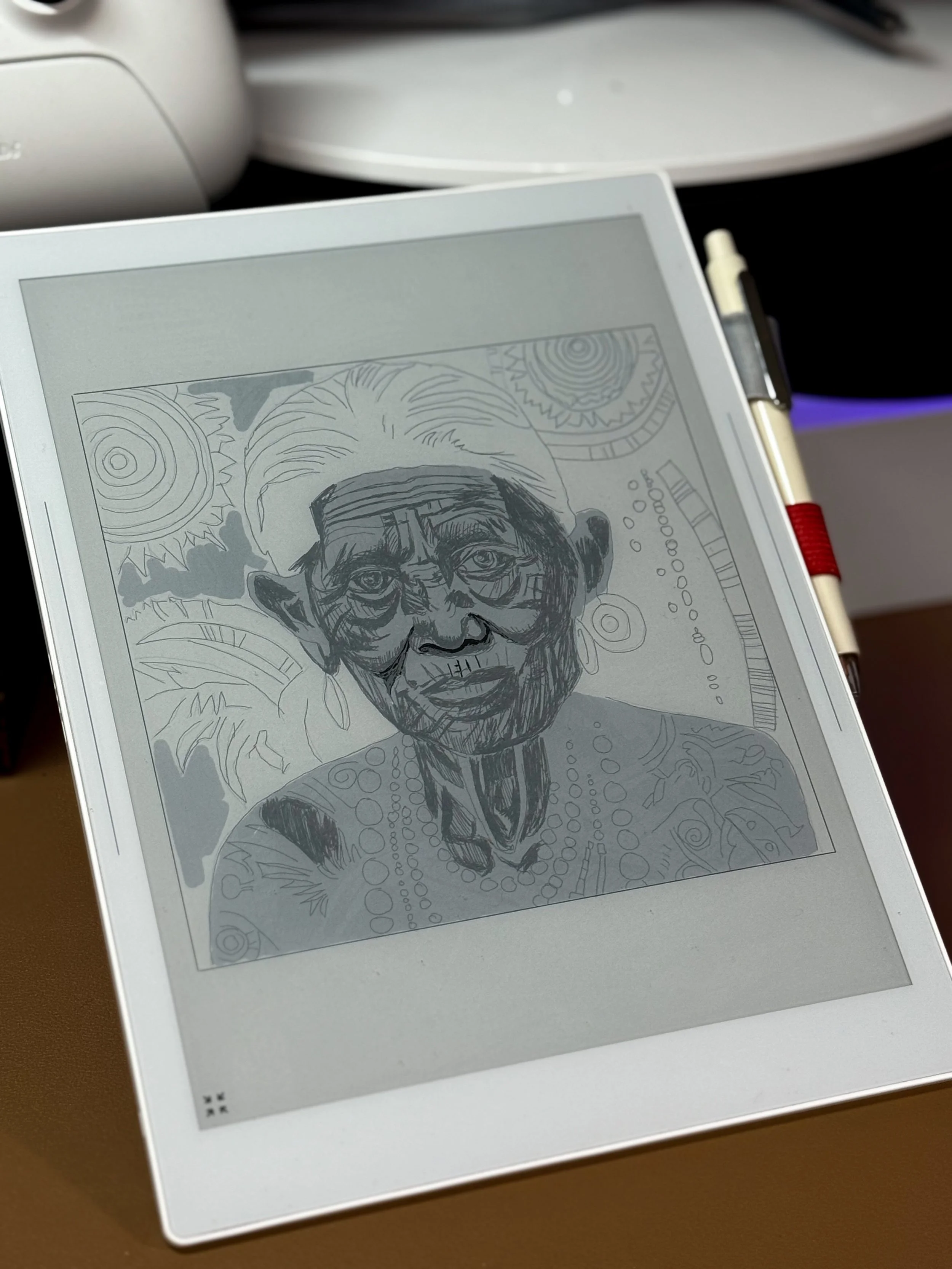

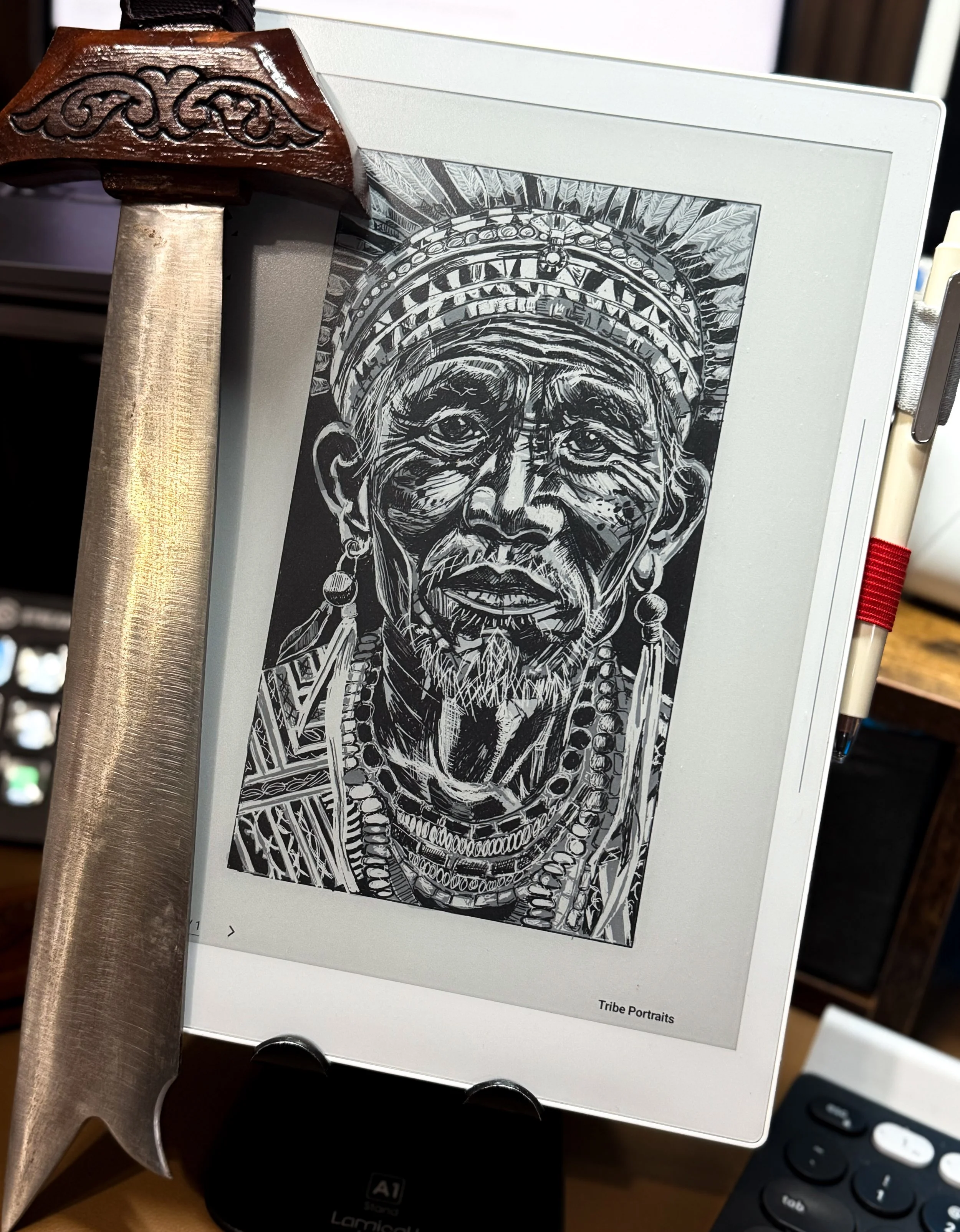

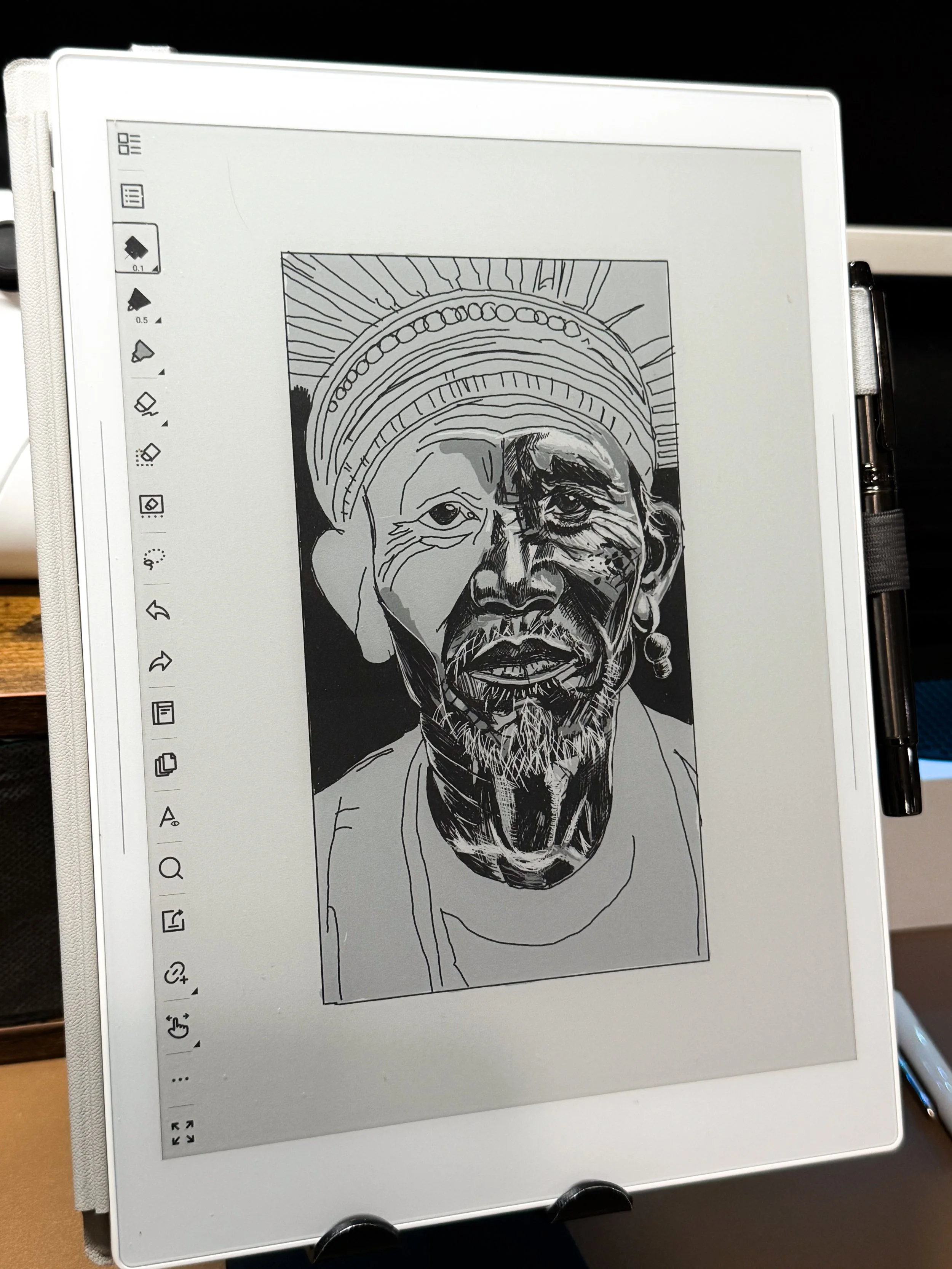

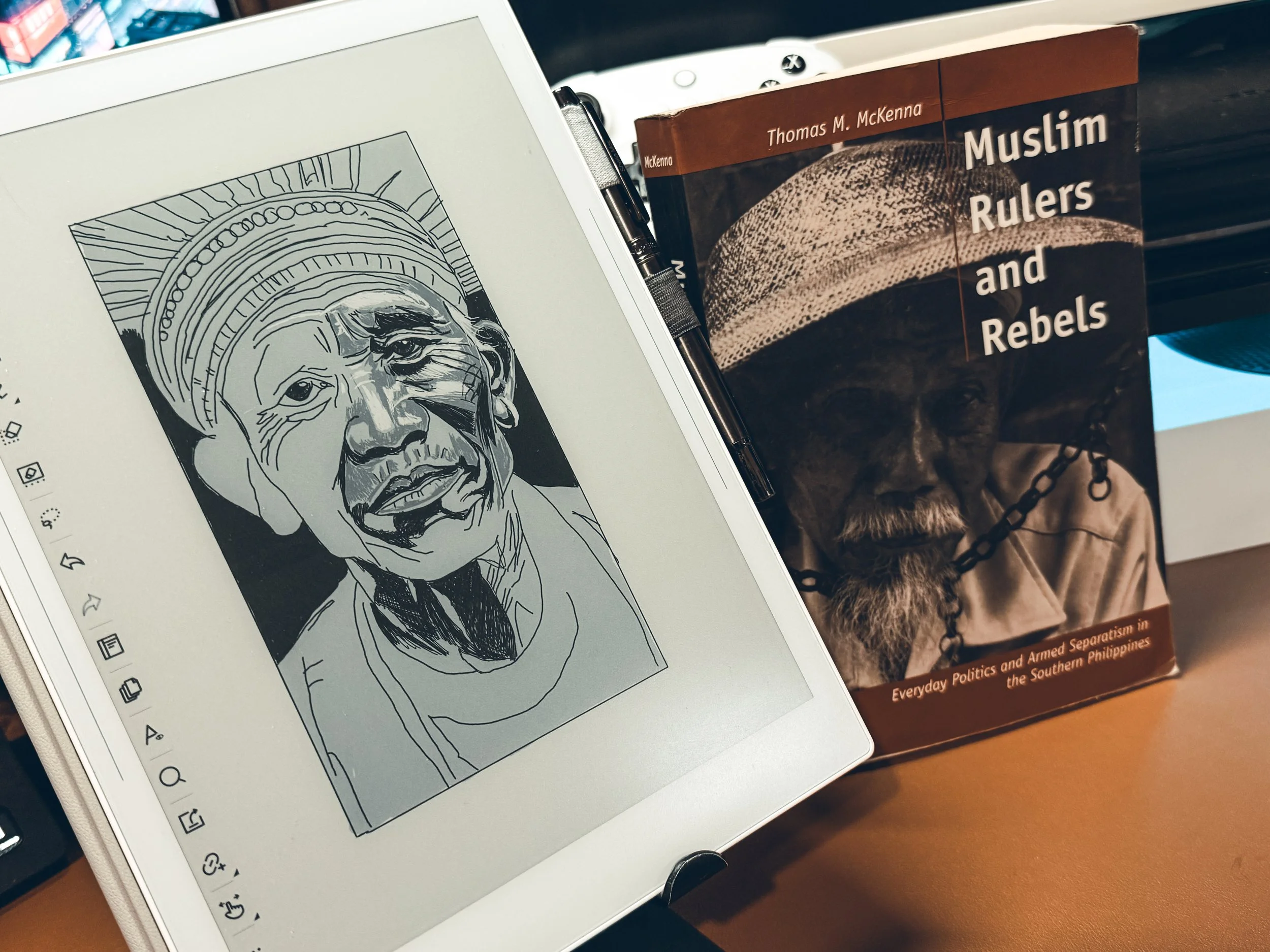

Isnag (Isneg): River Country, Lapat, and a History Transformed

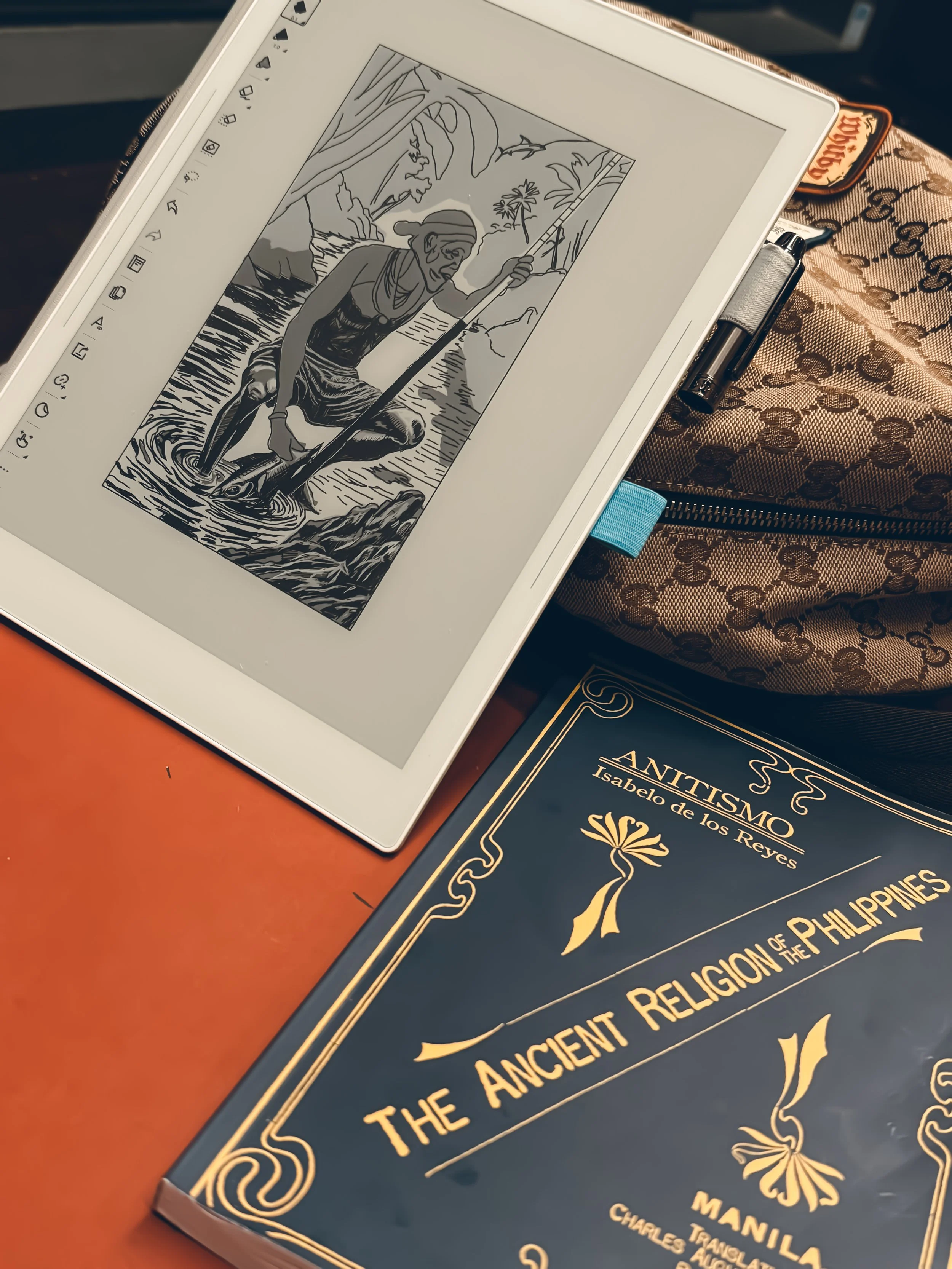

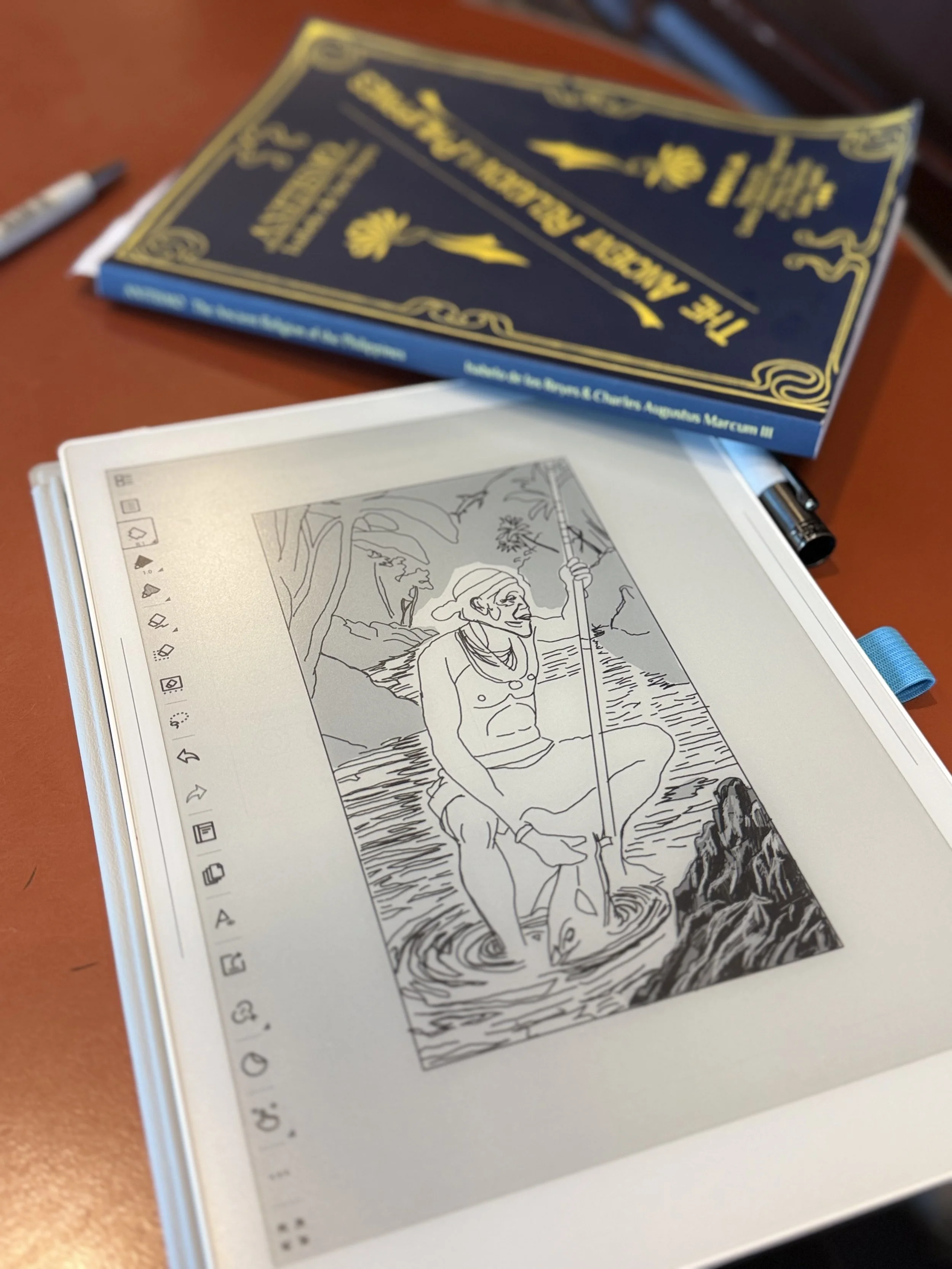

In the northern highlands of Apayao Province, the Isnag—also widely spelled Isneg—are often described as a people shaped by river valleys and mountain terrain. Their communities have long been linked to waterways that served as routes for settlement, travel, and livelihood in a rugged landscape.

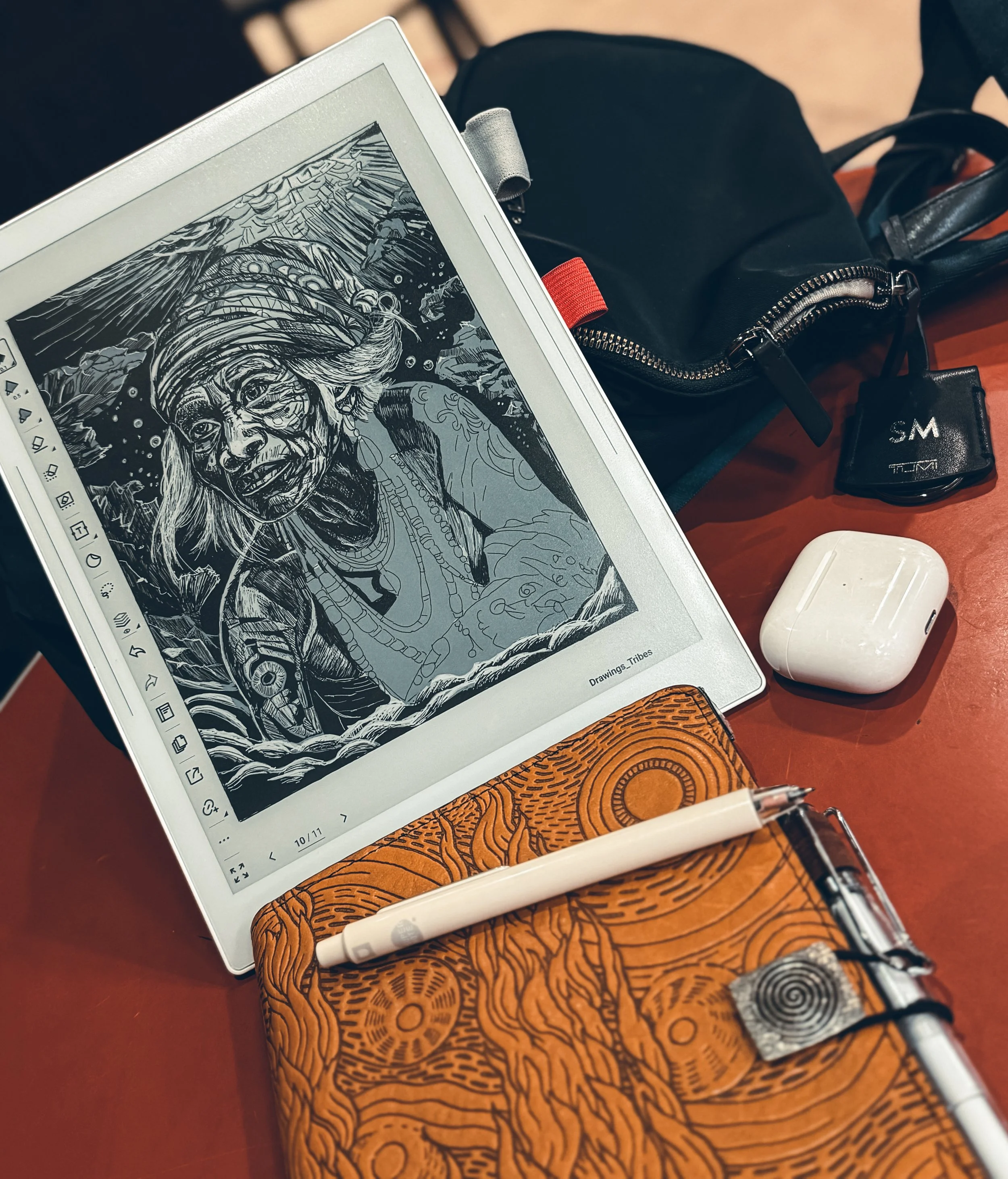

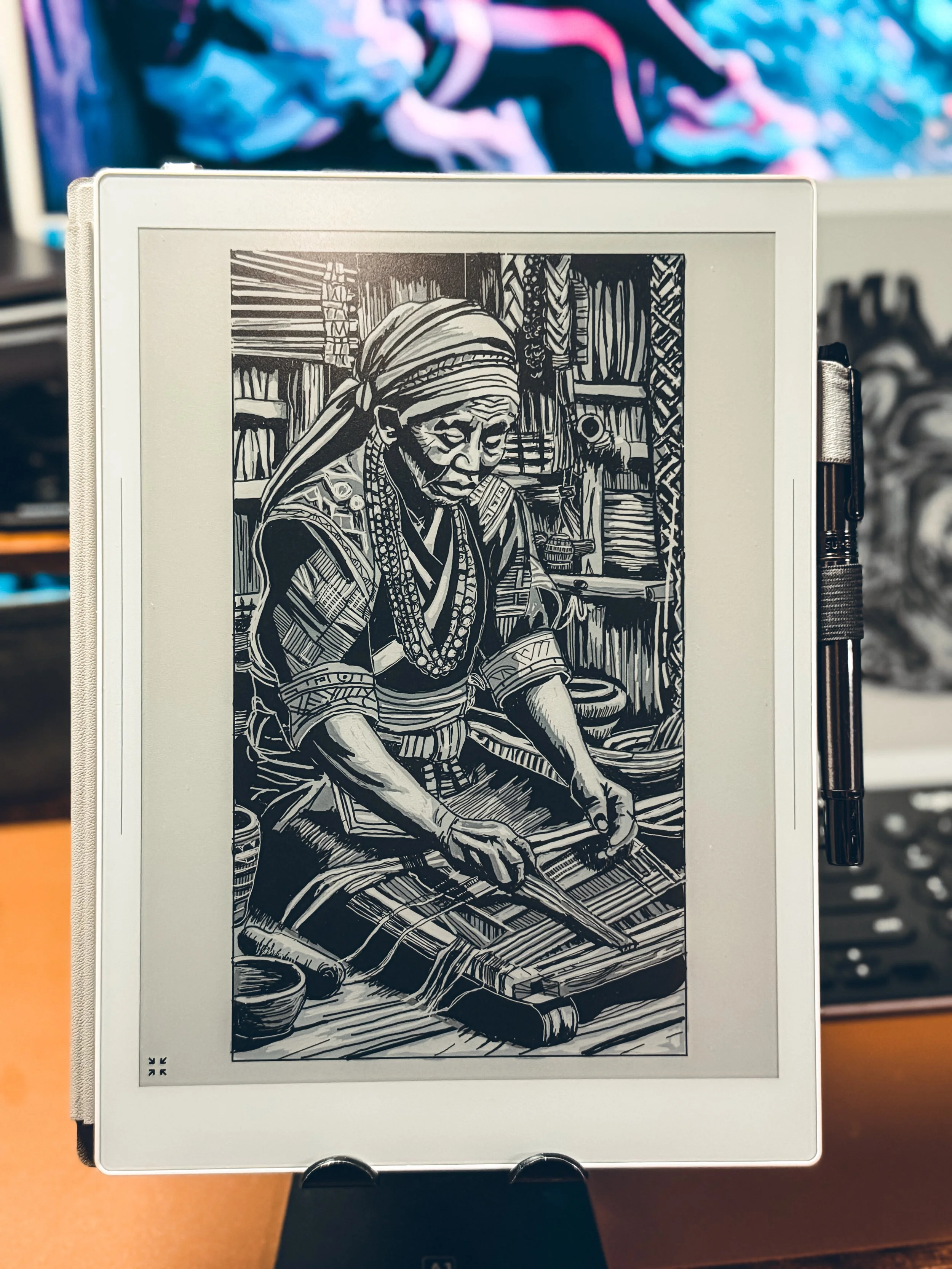

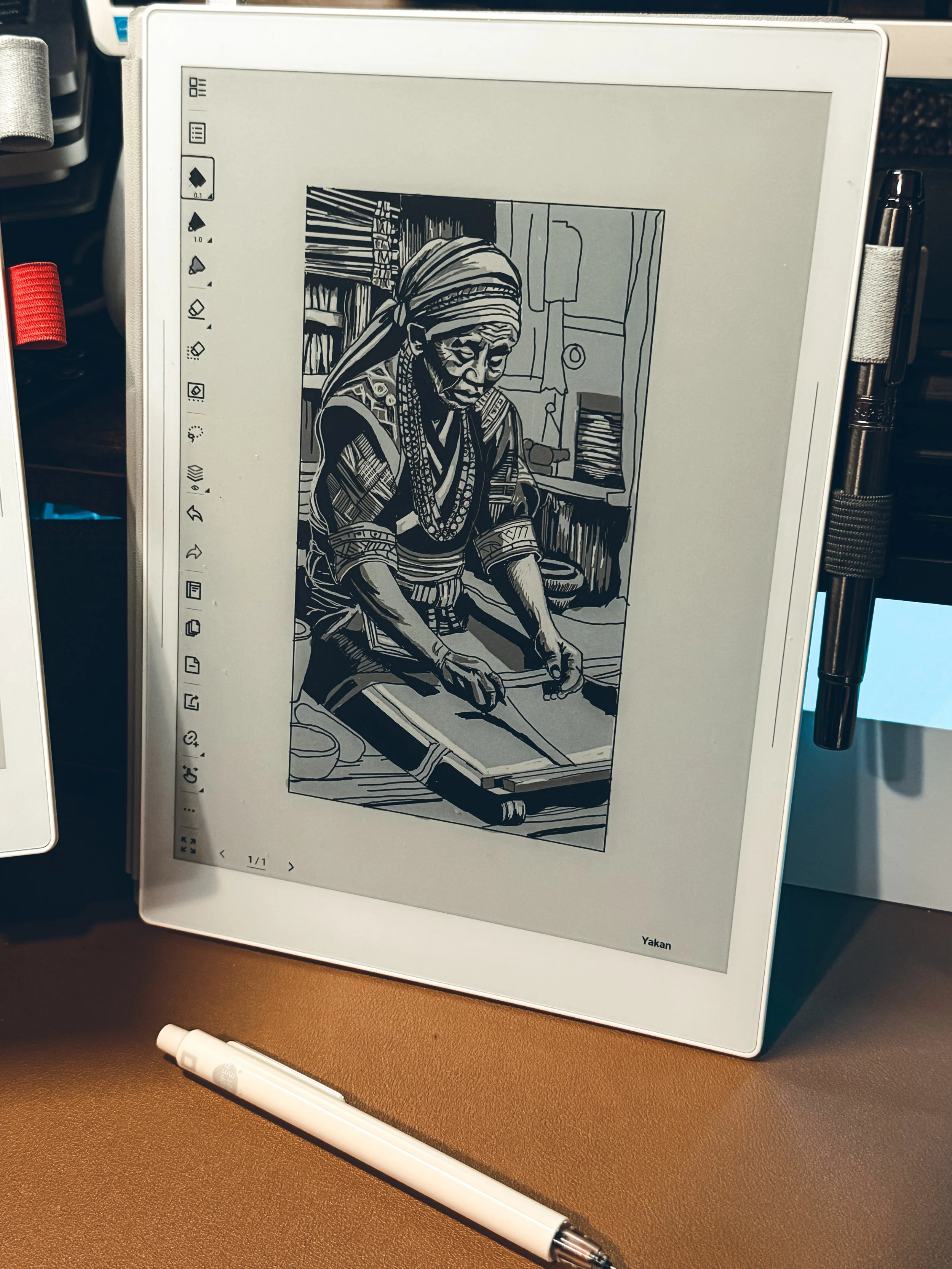

A central cultural practice associated with the Isnag is lapat—a customary rule of restriction that sets specific areas as off-limits (temporarily or by community decision) to protect resources and allow forests, rivers, and hunting grounds to recover. It’s an Indigenous system of stewardship: conservation enforced not by distant policy, but by shared agreement and accountability.

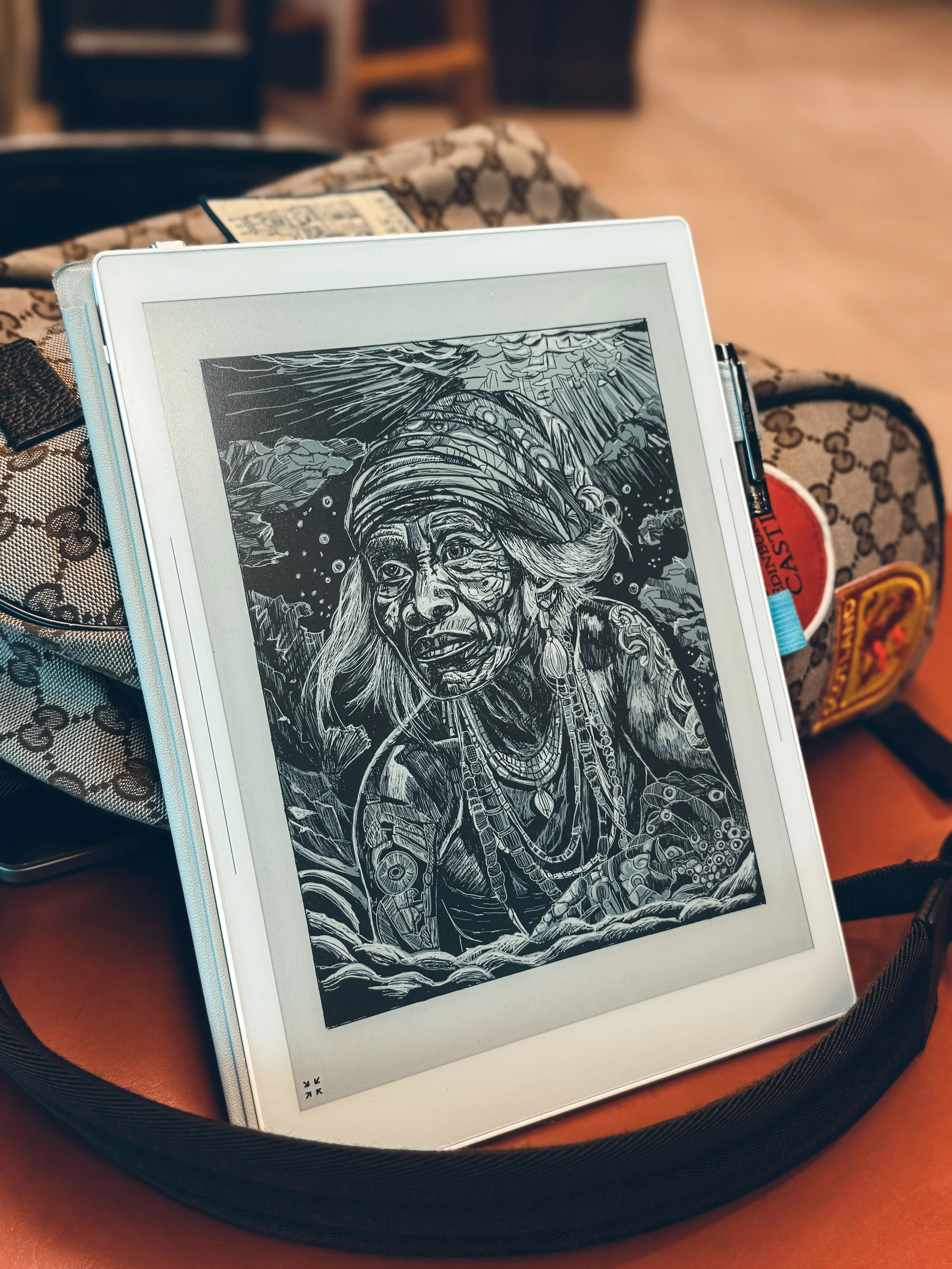

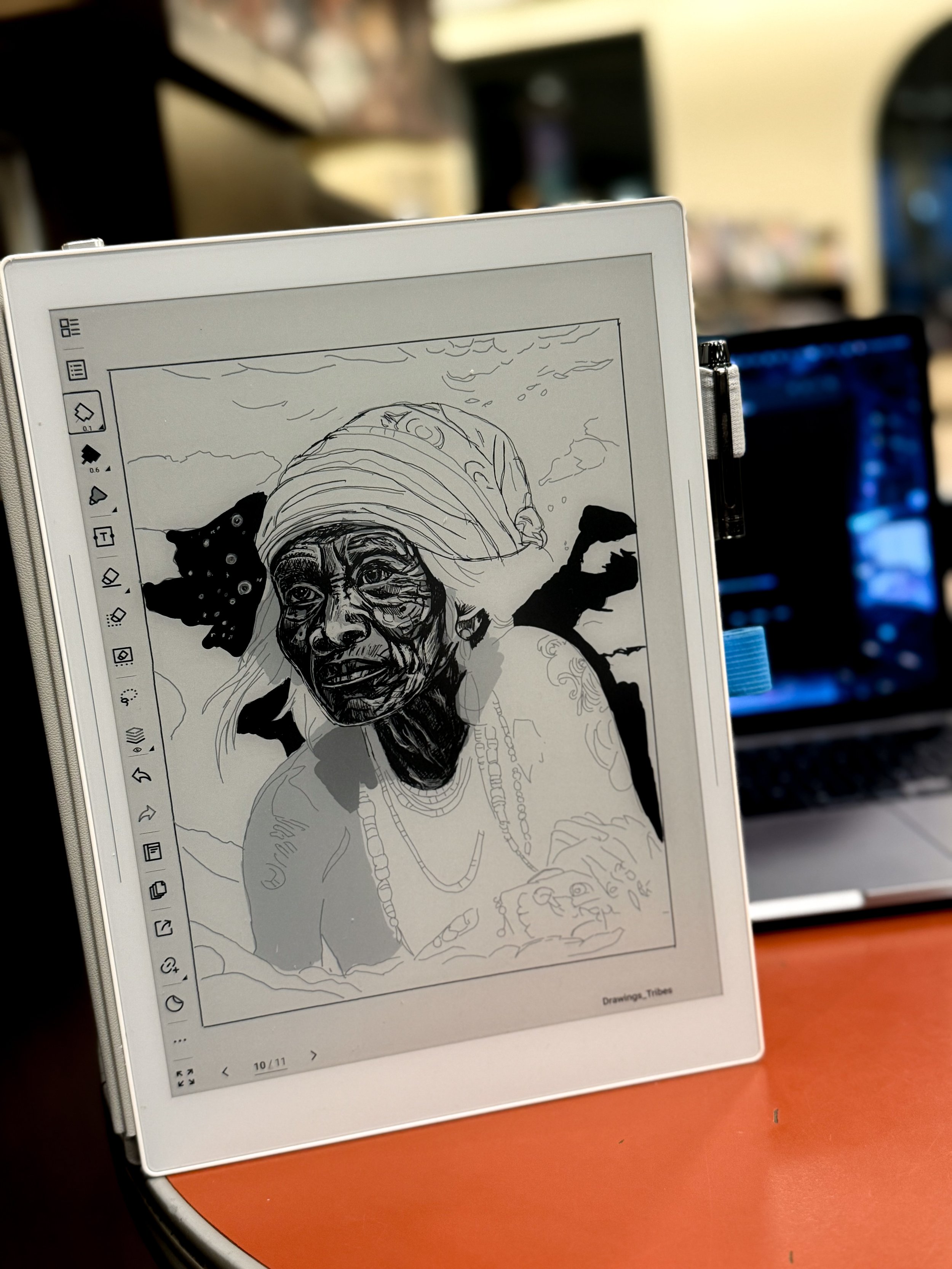

Older ethnographic and historical accounts also record headhunting (head-taking) as part of the region’s past, including among communities identified as Isnag/Isneg. In those accounts, it is tied to cycles of conflict, revenge obligations, and warrior status—realities of survival in earlier periods that should be described plainly, not romanticized. Importantly, this is treated as a historical practice rather than a defining feature of Isnag life today.

Taken together, these threads show a fuller portrait: a people rooted in river country, guided by community law like lapat, and shaped—like many societies—by historical eras that included conflict and change. In the present, discussions of Isnag identity are far more often centered on cultural continuity, homeland, and the protection of land and water that continue to sustain community life.

Next up->